Thursday

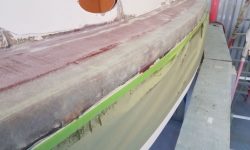

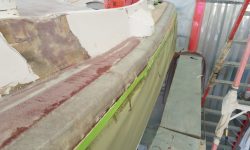

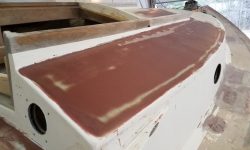

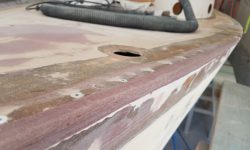

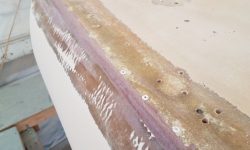

I sanded the new fiberglass on the starboard hull/deck joint and across the transom, and also sanded the first round of fairing compound on the port side.

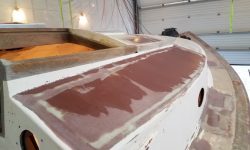

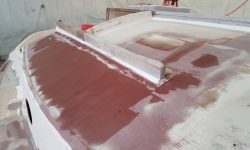

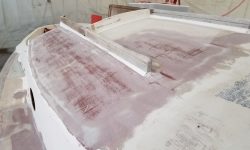

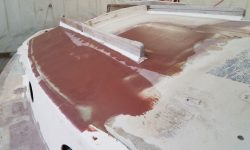

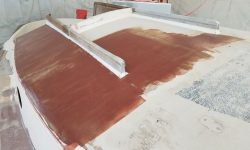

On the coachroof, I sanded off most of the old paint and did what I could at this point to even out the surface, my next step towards improving the appearance and finish of this large area. I had to strike a balance between how much paint I could remove and how much to sand the fiberglass surface, since the paint had been applied without benefit of any fairing or smoothing and there were numerous areas where the paint was deep in the weave of the cloth and other low spots.

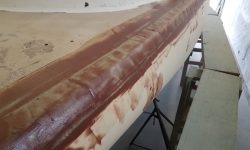

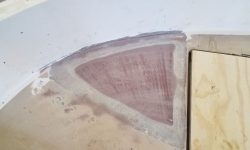

After cleaning up from the day’s sanding efforts, I applied epoxy fairing compound to the hull/deck joint as needed, with the first coat on the starboard side and transom. With the second coat on the port side, I used a wider trowel to continue the overall fairing efforts on the rebuilt sidedeck (and other areas as needed), incorporating it into the new hull/deck joint.

Total time billed on this job today: 8.25 hours

0600 Weather Observation: 55°, mainly cloudy. Forecast for the day: Clouds and sun, showers, around 70 but becoming cooler in the afternoon