Before starting on the prep work at the hull-deck joint/rubrail, I removed a tank vent fitting from the port quarter, as the fitting would soon be in the way. The fitting was only hand-tight and easy to remove, and I stuck the vent back in the hose inside the locker for safekeeping.

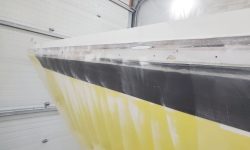

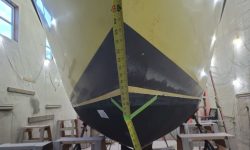

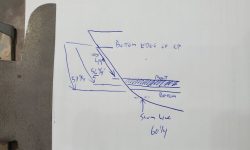

The black sheer strake was molded so as to be slightly proud of the rest of the hull, approximately 1/8″, but at the ends the protrusion tapered off to nothing a bit below the old rubrail location. To aid in recreating the shape later on, I took the time to make patterns of both the stern and bow on the port side; I could flip these for the starboard side so saw no need to make specific patterns for each corner. I also made a rubbing of the Ericson logo on the quarter in case it needed to be recreated later.

Before continuing, I closed up the companionway and other hatches to keep dust out of the boat as much as possible.

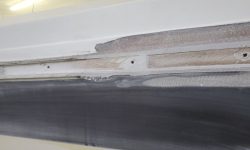

I spent the remainder of the day grinding the out-turned hull and deck flanges flush (or as nearly so as possible) to their adjacent surfaces. At the deck side, I also removed the gelcoat up as far as a molded “character line” in the toerail/deck edge, which logic and practicality dictated would probably be the end point for new tabbing in this instance. More on this later. I brought the flanges as flush as possible with the hull and deck moldings on either side, but had to balance this with removing too much material from the center, where the wooden strip had been and where other structural material, including interior tabbing and some kind of adhesive filler material, needed to remain in place.

Hull and deck moldings rarely, if ever, are perfectly fit and symmetrical all around, so some misalignment is standard; this is one reason manufacturers use external rubrails or trim to cover the seam. I’d make up the differences, where needed, with epoxy filler to bring things flush all over before tabbing over the seam, but essentially and practically speaking I ground the old flanges flush all around. I didn’t use the grinder for anything beyond the minimum required to remove the bulk of the material, and would finish up sanding and surface preparation with less aggressive tools to avoid excess fiberglass removal and maintain the existing contours of the moldings to minimize future fairing work. This all made a bit of a mess, but with more sanding in the immediate future I just gave the hull a quick blow down, leaving the rest of the shop for cleaning later in the week.