Over the weekend, the owner finished up hardware removal on deck, including the port frames and cockpit coamings. One of the jobs on the list coming up is to remove the existing winch islands at the cockpit and rebuild the sidedecks as needed to replace them. The “floors” inside these islands were badly-rotted plywood and, rather than attempt to find a way to repair them, the owners chose to reconfigure the decks and use stand-alone winch stands to support the winches. All this would happen in due course once I started work on the decks.

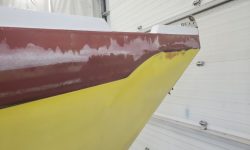

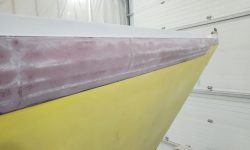

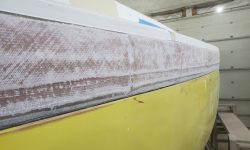

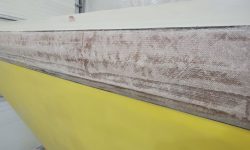

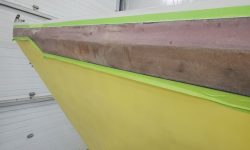

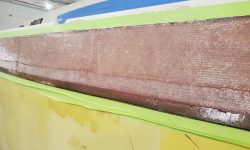

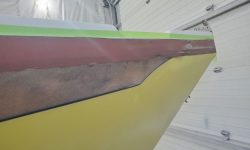

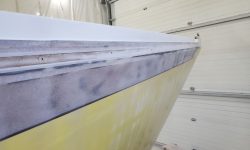

In the meantime, my focus remained on the hull. I began the day with a round of sanding to clean up the epoxy fill material I’d applied to the hull-deck joint last time.

As expected, this left various low spots requiring another round of epoxy filler. The more fair the area was before applying the fiberglass over the joint, the more fair the fiberglass would be thereafter, making finishing the joint that much easier. I used a wider trowel as needed over portions of the seam in the midships-to-quarter sections of the boat to bring the whole area more fair from top to bottom in these “flattest” areas of the boat.

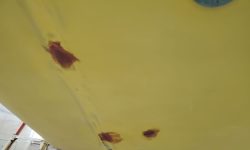

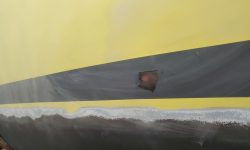

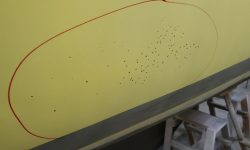

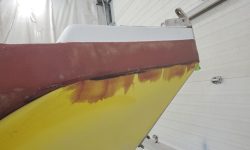

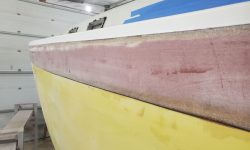

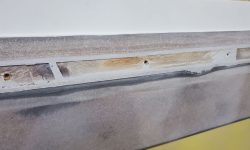

In the afternoon, with nothing more I could do at the rubrail for now, I got to work sanding the topsides to prepare them for minor repair work and eventually primer and paint. The topsides were original gelcoat–including the striping–and despite oxidation and wear from close to 50 years of life, were in generally good condition and wouldn’t require heavy sanding or paint removal. I chose my 6″ orbital finishing sander for the job, and chose also to start with the bow sections on both sides, as I think the bows are the part of the boat I like sanding least of all, so best to get them out of the way. I began at the waterline, working from floor level, and sanded up as high as I could (about a sanding pad’s width above the boottop) from the bow stand on the port side around to the same place to starboard. I also removed an inch or two of the bottom paint to help ensure I had a clean and smoother area to apply tape later on. I worked through 60 and 80 grits with the sander: 60 to break the surface, and 80 to smooth from there. Sometime later, after various minor repairs, I’d go over everything with 120, but that was later.

Once I was finished from floor level, I sanded the remainder of the topsides in these sections, bringing me to the end of the day.