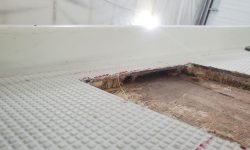

I removed all the clamps and sandbags from the core and other new work, then water-washed as needed to prepare for sanding. I used a chisel to lightly scrape away the hot glue and support sticks from my inner-skin patches, but unfortunately the patch at the port aft tank fill opening failed; it was clear from its appearance that it had never stuck to most of the area around the opening in the first place. I made alternate plans to cover this smaller hole.

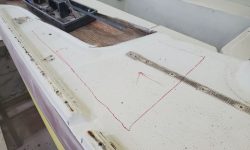

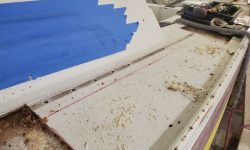

Next, I lightly sanded the fresh core and other areas just to remove any hard spots or epoxy ridges and to prepare the cored areas for eventual fiberglass. I cleaned up the fiberglass patches over the round holes with a small rotary sander, and then, while I was at it, used a grinder to remove gelcoat and taper the laminate inside the cockpit in way of the edges of the old winch island areas, preparing these areas for eventual laminate. My plan was to wrap a couple layers of the new top skin over the inside edge of the cockpit, tying it into the laminate below. There’d be a bit more work ahead on this corner later, once the core was in place.

To finish off my sanding of the moment, I prepared the exterior side of the three through hull holes in the counter as well. Then, I cleaned up the boat and shop to give me good working conditions for the rest of the day.

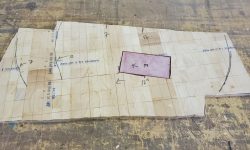

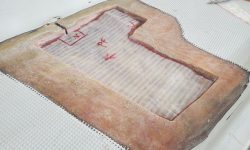

Once I’d cleaned up, my first order of business was to pattern the core for the two small after sections, just forward of the transom. With that done, I could go ahead and fill the patches flush with the surrounding inner skins, and lay a strip of thin fiberglass over the 2″ tank fill opening from the top; there was ample room in the space for the fiberglass without affecting how the core would sit. I also filled flush the similar repair at the stem, though I apparently didn’t take a picture.

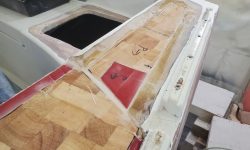

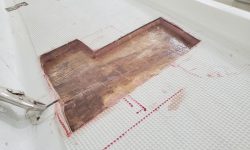

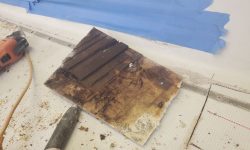

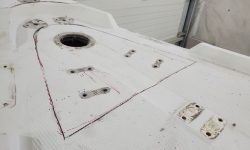

While that material gelled, I worked to finish up the prep on the new core for the areas outboard of the cockpit. I dry-fit the pieces once more to ensure they fit properly with the new fiberglass edges now in place, then marked the winch locations on the starboard core, as I’d done before with the port, so I could omit some of the core where the winch stands would land. To ensure a consistent measuring datum, versus using the cut line from the old winch islands’ removal, I determined these positions with the tape held against the bottom of the molded coaming block at the forward end for later duplication. Then, down on the bench, I cut pieces of 1/2″ prefab fiberglass to appropriate sizes, and cut out the core in the various areas to accommodate the fiberglass, including sections in way of the forward stern pulpit bases on the two smallest aft pieces.

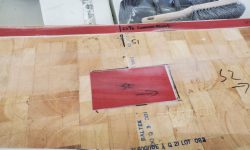

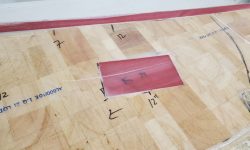

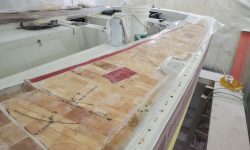

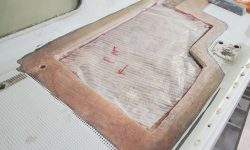

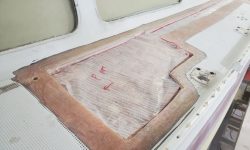

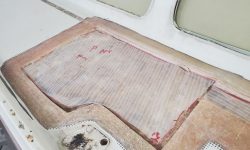

After final preparations and cleanup, I installed the new on both sides outboard of the cockpit, along with the piece on the foredeck. I happened to need to change my gloves during the process, leaving me clean and able to take a few pictures right after epoxying the core in place and before covering and weighing down. I didn’t have enough sandbags to cover the foredeck section, so I used whatever weights I could conveniently find.

To round out the day and week, I finished up by making paper patterns for the fiberglass laminate over the previously-cored areas on the sidedecks.

While I was working nearby, I happened to notice this oddity of note at one of the old snap locations for the existing dodger on the side of the cabin trunk: a cheap plastic drywall anchor. I’d seen many things over the years, but this was a first in my experience.